I’m not saying that we should do it, all I’m saying is that maybe we could do it. This is obviously just a thought experiment. Legality aside, most of the options I’m going to mention would be highly immoral and probably deadly for the animal. Basically, what I’m saying is don’t try this at home. Now that I’ve got my disclaimer out of the way, let’s get into it.

The first and most important question here is “Could we make a dinosaur?” The short answer is no, but actually yes. The Jurassic Park movies popularized the idea of cloning dinosaurs, so we can look into that prospect first. In order to clone an organism, the bare minimum requirement is that you have some of its DNA. Prehistoric mosquitos frozen in amber would probably just give you mosquito DNA, so dinosaur fossils would be a better place to look. There have actually been a few attempts to extract DNA from dinosaur fossils, which Paleontologist Jack Horner explains well in his TED talk, but none of them have been successful. One attempt even involved building a portable lab at the fossil dig site, so that the DNA could be extracted as soon as the fossil came in contact with the air. Even this elaborate setup resulted in failure. It seems like cloning a dinosaur wouldn’t be a valid option, so it may be impossible to make a perfect replica of a dinosaur exactly as they lived millions of years ago. However, it might be possible to reverse engineer a dinosaur-like creature using developmental biology and genetics. Let’s walk through the steps.

Because we aren’t building a dinosaur from scratch, we need a starting animal to base everything off of. At this point there is no debate that birds evolved from a dinosaur group called the theropods, which included most of the two-legged dinos like velociraptors and t-rexes. Since birds are the closest living relatives to dinosaurs, we’ll use them as our template. Chickens are often used in developmental biology research, so we’ll stick with chickens for this example, but if you want a bigger, badder dino you could swap the chicken out for something like an ostrich or a cassowary.

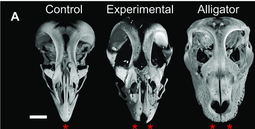

Now that we’ve got our starting material, let’s begin changing it up. The first feature that needs modification is the beak. The distinct shape of a bird beak is made of a material called keratin (the same material as fingernails and hair), but we want the more rounded snout shape of a dinosaur. There have actually been some studies that found a way to do this exact thing. The scientists in this experiment showed that a gene called fgf8 is turned on more than usual in the face/beak area of developing chickens.1 When this gene is experimentally turned off during face development, the chicken instead forms a snout-like feature, more akin to an alligator or a dinosaur. So, in order to give our chicken a snout, all we have to do is turn off the fgf8 gene in the beak area.

We have a functional snout now, but what’s a snout without teeth? The ancestors of modern birds lost their teeth a long time ago (about 100 million years ago), and no birds alive today have teeth.2 Geese have a serrated, tooth-like structure called tomia, but this is made from the same material as the beak. Luckily, scientists have discovered a chicken mutant called Talpid that seems to cause chickens to go back to their ancestral ways of growing teeth.3 The idea of a single mutation changing 100 million years of evolution seems too good to be true, and in a way it is. The Talpid mutation is most likely lethal for the chick, so our experimental dinosaur wouldn’t survive. There are probably a lot of other genes that would need to be changed as well (for example, it seems that restoring enamel to hypothetical bird teeth would be near impossible),4 but this is just a thought experiment so I’m only focusing on the larger structures.

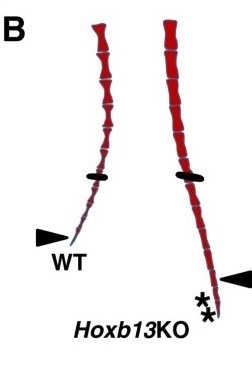

Apart from probably being dead from a lethal tooth mutation, the front side of our dino is starting to look pretty good, so let’s move on to the back. The next feature that we’re going to build is a tail. Ancestral birds lost their tails to help with flight but looking at chicken embryos shows that birds actually develop a full tail, and then completely lose it before hatching.5 This means that we don’t have to build a tail from scratch and instead just have to prevent the tail from being lost. This will take a couple of steps. First, we would need to stop the Hoxb13 gene from being active in the back of the bird. Experiments show that turning this gene off in the tail region causes chickens to keep two more vertebrae than usual. That’s good, but we’ll need about 13 more vertebrae in order to match what many theropod dinosaurs had. Studies have also shown that a chemical called retinoic acid (RA for short) is what causes normal chickens to lose their tails. Blocking this chemical in the embryo would allow the bird to keep its tail after hatching.

This is a pretty good looking theoretical dinosaur at this point. It’s got a snout, teeth, and a tail. But it feels like something is missing… Scientific consensus at this point is that dinosaurs (or at least the theropods) had feathers.6 And while it would be scientifically accurate to keep the feathers on our theoretical dinosaur, it would also look way cooler if we gave it scales. And this isn’t a perfect dinosaur replica anyways, so why not try to make it look awesome? I’ll at least entertain the idea and look at some ways to make scales. Giving birds scales won’t be nearly as difficult as giving them teeth because unlike teeth, which have been completely gone for millions of years, modern birds still have scales. If you don’t believe me, take a look at a chicken’s feet. In fact, many birds still have scales on their legs. There has been a lot of research into how scales evolved into feathers, but not many experiments have been tested to cause the reverse. Studies show the chemicals β-catenin and retinoic acid (among others) play big roles in turning scales into feathers.7 If the reverse holds true, maybe blocking these chemicals would cause scales to form all over the chicken, instead of just the legs. Then again, biology is rarely that simple, so only time will tell if this is the best way to give our experiment cool looking scales.

And there we have it: a dinosaur (-like creature). Obviously this isn’t a perfect replica, and it wouldn’t take an expert to know something is off. In reality our dino’s appearance would probably horrify people rather than amazing them. But it is a cool thought experiment. To me, the most incredible thing about this is that we can break down the major structural evolution from dinosaurs to birds in a few simple steps.

References:

1. Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S., et al. “A Molecular Mechanism for the Origin of a Key Evolutionary Innovation, the Bird Beak and Palate, Revealed by an Integrative Approach to Major Transitions in Vertebrate History.” Evolution, vol. 69, no. 7, 2015, pp. 1665–1677., doi:10.1111/evo.12684.

2. Louchart, Antoine, and Laurent Viriot. “From Snout to Beak: the Loss of Teeth in Birds.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 26, no. 12, 2011, pp. 663–673., doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.004.

3. Harris, Matthew P., et al. “The Development of Archosaurian First-Generation Teeth in a Chicken Mutant.” Current Biology, vol. 16, no. 4, 2006, pp. 371–377., doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.047.

4. Sire, Jean-Yves, et al. “Hen’s Teeth with Enamel Cap: from Dream to Impossibility.” BMC Evolutionary Biology, vol. 8, no. 1, 2008, p. 246., doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-246.

5. Rashid, D.J., Chapman, S.C., Larsson, H.C. et al. From dinosaurs to birds: a tail of evolution. EvoDevo 5, 25 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-9139-5-25

6. Xu, Xing. “Feathered Dinosaurs from China and the Evolution of Major Avian Characters.” Integrative Zoology, vol. 1, no. 1, 2006, pp. 4–11., doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2006.00004.x.

7. Wu, Ping, et al. “Multiple Regulatory Modules Are Required for Scale-to-Feather Conversion.” Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 35, no. 2, 2017, pp. 417–430., doi:10.1093/molbev/msx295.